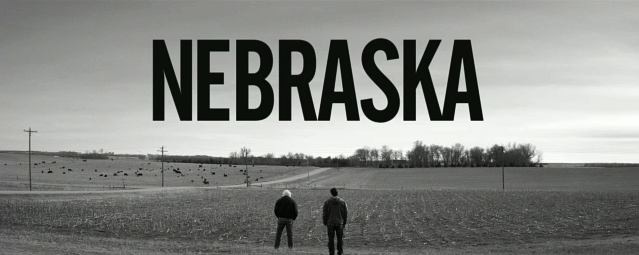

directed by Alexander Payne (2013)

Nebraska was my first VIFF gala and what a great way to start off the 2013 festival. I predict Oscars for both Alexander Payne, and Bruce Dern - at least nominations, if not the actual awards.

It's such a warm, touching flick. At times hilarious, while others will make your heart all squishy. I liked it so much, when I got an invite to a promo screening, it was a no-brainer to see it again. I enjoyed it just as much the second go round, but I took more notice of the values it both criticized and exalted.

It's a beautifully human film, that visually stuns with Phedon Papamichael's Walker Evans style, B&W cinematography. He packs it full with long static shots of endless prairie vistas and medium shots of small town, and rural life, that imbue the stark imagery with a retro longing quality for times gone past. It made me oh so homesick and nostalgic for the prairies. It has a lovely instrumental soundtrack too, produced by Mark Orton and the rest of the Tin Hat Trio rebanded, (as Tin Hat), for the first time since 2005, to create their varied takes on American roots music.

Alexander Payne is known for his relationship tales, and usually they involve more upper and middle class protagonists - this one is a little more down to earth in portraying rural farm folk, and small town people, but it still contains the same acerbic criticism, and upholding of certain values of Payne's other flicks. There's a privileging of the values of the have mores, over the lesser blessed. And although there is much criticism, ultimately, the ideals of patriarchy and it's egoic concerns, are implicit in the content and resolution of conflicts within the plot.

The plot is simple. The Grants are a small family of 4 living in Billings Montana: David, an electronics salesman, (Will Forte), his older brother Ross, a local news caster (Bob Odenkirk,) their parents, Kate, a former hairdresser, (June Squib), who is a reductive caricature of the foul mouthed, and hostile nagging female, that constantly hectors everyone, especially the silent and stoic alcoholic father, Woody, (Bruce Dern) who suffers from the effects of Alzheimer's. Woody believes that he has won $1,000,000 through a magazine sweepstakes mail out, and wants to collect his winnings in Nebraska, since his family is unable to convince him that the sweepstakes is a scam. Much of the humour in the film is through the interactions with their extended family. Woody is the youngest of 7 brothers, and his brothers never left the small town of Hawthorne, Nebraska, where they grew up.

What struck me most in the film, was how selfish everyone was regarding their actions with one another. Everyone kept a ledger that was very unbalanced, noting only where they gave, and not when they benefitted from the generosity of others. This attitude reflects the American ideal of the so called self made man, which in turn gave rise to the disconnected nuclear family, all of which are based on the hierarchical patriarchal mode. There is criticism of this mode, but acceptance of its primacy is ultimately supported through the actions of the characters.

There is a exploration and dismissal of the value of fairness in the film too. There is a distinct differentiation between wealth that is perceived as earned or unearned. The recognition of fairness is something that is innate, and not just to humans - we are born with a moral capacity to judge others for their behaviour around fairness, and William Damon's 1970's studies demonstrated that equality bias in how children would rather something of value be destroyed than see it unfairly divided. The operational modes that dismiss these values are supported by many factors and over the course of the film the justifications and reasons behind the foibles of the main characters are revealed.

Stacy Keach's character Ed Pegram, reminded me of my father with his aggressive macho posturing. Pegram was a prime example of the selfish perspective - yeah this is a the nature of being human - we see everything through the lens of our own needs, but in this instance the relative wealth of his old partner became intolerably unfair. As Ed puts it, the windfall money Woody didn't even earn - it wasn't right that Keach didn't have a stake in it. From his perspective, he had given more to Woody than he got, so he was the victim! The fact is, when you look at things from a relative perspective, it's always possible to cast oneself in the poor unfortunate category, vis-a-vis another. And doing so justifies selfishness. It's just as easy to see yourself as better off, but that will generally create discomfort, and since the idea of fairness is so ingrained, we come up with reasons to justify inequity - based on merit and personal accomplishment.

When Will punches Ed in the face, I guess we're supposed to cheer at the old bully getting his comeuppance - an eye for an eye and all that. But the way Ed's face fell when he saw how carefully Woody folded the letter and placed it in his pocket, it was apparent that Ed understood that he'd been being needlessly cruel to an old befuddled man. Ed looked ashamed. This could have been a moment for transcendence of the violence as a resolution to conflict model, but no. David's measured and deliberate response plunges us back down into the usual old egoic macho competitive concerns. David defends his dad's honour and decks an old man. The young bull pushes the old one out of the dominant position. It doesn't represent any kind of change really, just a change in who's doing the bullying.

What are the roots of the silence and stoicism of the Grant men? Could it be they are all PTSD traumatised from their war experiences? Could the very model of masculinity that demands they maintain a dominance over the earth and everyone else in their lives, women and children included, and also a similar control over their devalued "feminine" feelings be the cause? When one of the wives tells Woody that his brother has an injured foot. The brother's response? "It's ok. It just hurts." Rigid gender roles do hurt - men and women both. The Grant cousins Bart, (Tim Driscoll) and Cole, (Devin Ratray), delight in showing dominance over their cousin David's leisurely drive to their town from Billings. They operate out of a competitive, zero-sum, paradigm. You're either on top, or on the bottom - there's no such thing as equality. In addition to being of lower consciousness, they're low status too - unemployed, and most troubling, they're also convicted sex offenders doing community service for rape - though they and their mother deny that reality. And of course the denial of rape culture is very strong everywhere, but especially in this conservative family values community, the acceptance of men hurting women seems to be par for the course. In fact there is a de-facto acceptance of violence in many forms, though from the females it's more verbal. Kate is very vicious in her treatment of everyone - she's always been a bitch as Ed flat out tells David. Women who exert any form of power, especially sexually, well they're sluts and bitches ain't they?

The old homestead, that was hand built by the grandfather with the help of his brothers, had been abandoned and left to moulder back into the land. The value of family helping one another - these are what Payne seems to be championing throughout the film, that mythical past of living on the land, "salt of the earth" as Kate references one family, is not a lost utopia either. Here too, there's rot in the foundations of that patriarchal model. When Woody is in his parent's bedroom, he says "I would get whipped if they found me in here." He seems oddly nonplussed when he says, "There's no one here to whip me now." The reins of power in the hierarchical patriarchal model are those very same same whip hands that subjugate.

And the satisfying moment in the film where you discover how much Woody wanted to be the provider of THINGS for his sons - sure he wanted a truck and a compressor, but mostly he wanted to leave the money for his boys. He was ashamed that he had failed to provide for his grown up sons, long out of the house and living their own lives. David tells him he shouldn't worry about that, they're fine and he turns the tables and provides for his father those totemic objects of desire. The satisfying resolution of the film is when Woody gets to act as if he won a million dollars; he's driving down his old hometown streets in his prize winner hat, waving to the folk and leaving them with the impression that he's now a rich man. What does this illusion support? The idea that what other people think is MORE important that truth. That it's a pretty great thing to pull a fast one, and have the appearance of relative success, then lord it over the folk and community you abandoned before you take off with all that supposed unearned wealth. Of course it's just a fantasy version of doing that, but there's still something really smug and soulless in taking pleasure in the idea of simultaneously thumbing your nose and humble bragging about wealth.

And what of the road not taken? Ed tells David he wouldn't have been born if not for his intervention - Ed was the one who convinced Woody to stay with Kate instead of leaving her for the woman he loved - as Ed describes her "a halfbreed from the reservation."

There are only 2 instances of POC in the movie, this off hand and derogatory mention of a Native woman, and a scene where Woody goes to the garage he used to own. The first reference is a brief example of the NDN standing in for freedom and spiritual truth, which of course patriarchy does not allow. Hohum. In the 2nd, there are 2 Hispanic, presumably Mexican immigrant men working in Woody's old garage and Woody's attitude towards them is judgmental. He dismisses them, saying "They don't know what they are doing." This is an almost invisible recognition of the racist realities of rural white bread America's hostile reaction to the increase of POC in the population.

One of the most poignant scenes of what could have been, arises near the end when Woody is driving through the town saying goodbye. He passes by Peg Nagy, (Angela Mcewen), the woman he dated before he met the woman he'd spend the rest of his life with, and the expression on her face at his leaving was one of tender longing and contemplation for that imaginary life of love they could have had. Made my heart rise in my chest.

There was one scene that I had to ask the writer Bob Nelson about after the gala screening. Towards the beginning of their travels to Nebraska, David and Woody pass by a double locomotive with the engines coupled in opposing directions. This was such a perfect visual metaphor for the way Woody was at odds with his family, I wondered if Nelson had written it into the script. He hadn't, and he couldn't tell me whether it had been a deliberately created scene, or just one of opportunistic synchronicity. I lean towards the latter, but who knows, because there were a lot of visual puns, one which made me chortle aloud, when Woody and David take a leak on the roadside next to an farming irrigation apparatus.

|

| No they aren't peeing here:P |

The movie emphasises the value of love and support for your family, for good or ill, and that can be problematic if that enables selfish or self destructive actions, but honouring the values of acceptance, forgiveness, and above all love, are generally speaking, practices that have the potential to create a better place for everyone. I think the film overall is more an exploration of problematic values than supportive of the status quo, and it's really such a great flick in terms of the performances that I can't in good faith do anything other than highly recommend it.

No comments:

Post a Comment